High in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of northern New Mexico, where autumn aspen leaves flutter like golden prayers against the deep blue sky, a remarkable story of vision, perseverance, and pioneering spirit unfolds. This is the tale of how a German-Swiss immigrant with an eye for perfect snow and an unshakeable dream transformed a forgotten mining settlement into one of North America’s most challenging and revered ski destinations. It’s also the story of how that legacy continues to inspire today’s mountain adventurers, including the intrepid chilltravelers who find themselves guided through fall’s spectacular display by veteran mountain guide Joe LeBlanc, a man who has spent four decades reading these peaks like an open book.

High in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of northern New Mexico, where autumn aspen leaves flutter like golden prayers against the deep blue sky, a remarkable story of vision, perseverance, and pioneering spirit unfolds. This is the tale of how a German-Swiss immigrant with an eye for perfect snow and an unshakeable dream transformed a forgotten mining settlement into one of North America’s most challenging and revered ski destinations. It’s also the story of how that legacy continues to inspire today’s mountain adventurers, including the intrepid chilltravelers who find themselves guided through fall’s spectacular display by veteran mountain guide Joe LeBlanc, a man who has spent four decades reading these peaks like an open book.

The origins of Taos Ski Valley begin not in the high alpine bowls that would make it famous, but in the tumultuous Europe of the early 20th century, with a young man whose life would be shaped by war, displacement, and an unwavering passion for mountains.

The Forging of a Ski Pioneer

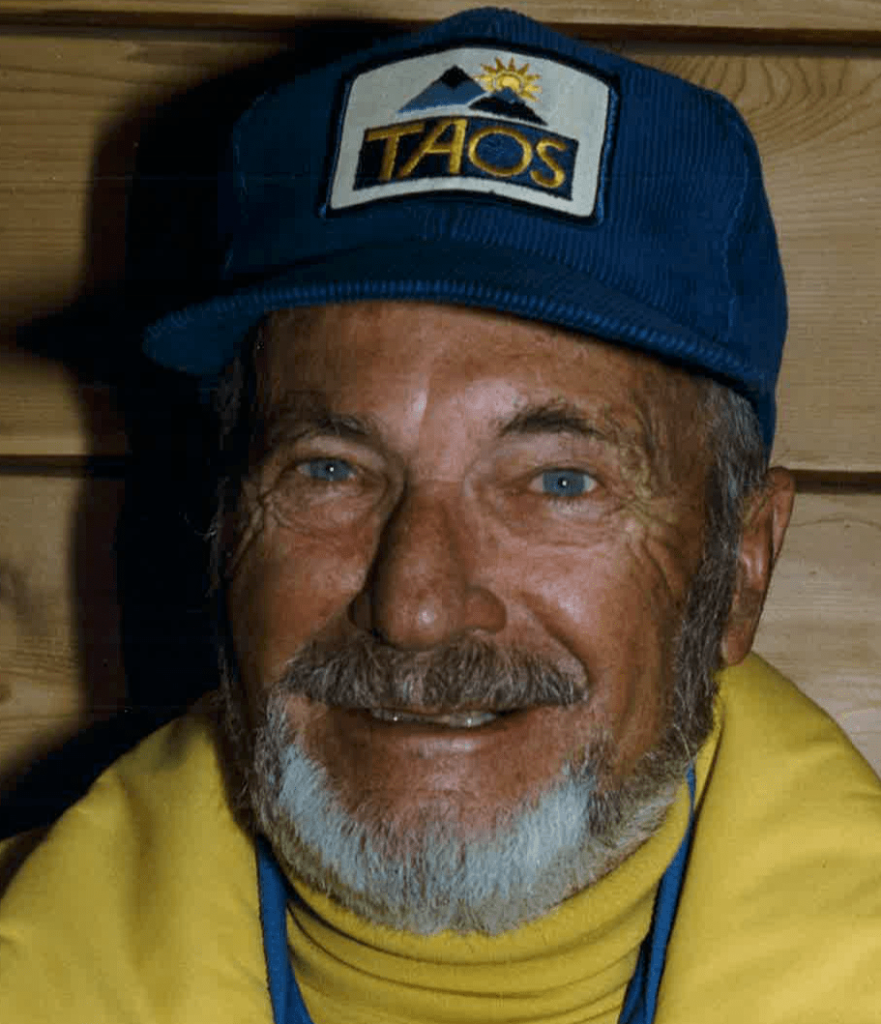

Ernst Hermann Bloch was born on March 24, 1913, in Frankfurt, Germany, to a family that would soon find their world upended by the rising tide of anti-Semitism. His father, Adolf Bloch, operated a successful felt and fur business that supplied hat manufacturers worldwide, including the iconic Stetson company, while his mother, Jenny Guggenheim Bloch, had served as a nurse during World War I before dedicating herself to raising their four children.

Growing up near St. Moritz, Switzerland, where his Swiss mother held citizenship, young Ernst was introduced to skiing at an early age. In Switzerland, skiing was mandatory for school-age children, and Ernst excelled not only at skiing but at numerous sports, from cricket to ice hockey. So gifted was he athletically that he would have easily qualified for the 1936 German Olympic ice hockey team, had it not been for his Jewish heritage—a cruel irony that foreshadowed the challenges his family would soon face.

The pivotal moment came with an unexpected visit from the Gestapo to the Bloch family home in Frankfurt. As Ernie’s son Mickey Blake would later recount, during the interrogation one of the agents suffered from an earache, and Jenny Bloch, drawing on her nursing experience, was able to provide relief. In gratitude for her kindness, the agent quietly warned the family that they needed to leave Frankfurt immediately. This act of unexpected humanity in dark times likely saved their lives.

In August 1938, the Bloch family immigrated to the United States, leaving behind their substantial home in Frankfurt—a property they could never sell in their haste to escape Nazi Germany. At age 18, Ernst had chosen Swiss citizenship and completed his mandatory service in the Swiss Air Force, a decision that would serve him well in the challenging years ahead.

From War to Western Slopes

Ernst’s first job in America was teaching skiing on the famous Saks Fifth Avenue snow trains that departed Grand Central Station for North Creek, New York, in the Adirondacks. These were no ordinary train rides—they were luxurious sleeper trains complete with bar cars and ski rental facilities, catering to wealthy New Yorkers seeking weekend mountain adventures. During weekdays, he operated a ski shop on Madison Avenue, establishing the foundation of what would become a lifelong dedication to the skiing industry.

Ernst’s first job in America was teaching skiing on the famous Saks Fifth Avenue snow trains that departed Grand Central Station for North Creek, New York, in the Adirondacks. These were no ordinary train rides—they were luxurious sleeper trains complete with bar cars and ski rental facilities, catering to wealthy New Yorkers seeking weekend mountain adventures. During weekdays, he operated a ski shop on Madison Avenue, establishing the foundation of what would become a lifelong dedication to the skiing industry.

The trajectory of Ernst’s life changed dramatically when he accompanied an Austrian friend on a cross-country drive to San Francisco, with stops at every major ski destination along the way, including Aspen, Colorado. This journey opened his eyes to the vastness and potential of American skiing, igniting dreams that would later crystallize in the mountains of New Mexico.

On New Year’s Day 1941, while skiing in Vermont, Ernst met Rhoda Limburg, daughter of a New York Supreme Court Justice. Their romance blossomed against the backdrop of a world at war, and it was Rhoda who would inadvertently guide Ernst to his destiny. During the summer of 1941, she invited him to join her in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she was studying art. Together they explored the high desert landscape, rode horseback through the arroyos, visited Taos Pueblo, and captured the dramatic vistas in photographs. This journey planted the seeds of what would become Taos Ski Valley.

When America entered World War II, Ernst faced his own battle for acceptance. Initially rejected by the 10th Mountain Division due to suspicions about his European background—the same military intelligence apparatus that feared he might be a spy—he persevered until the Army recognized his linguistic abilities and cultural knowledge. Speaking fluent English, German, French, and Italian, he was commissioned as an intelligence officer without attending Officer Candidate School.

The Army changed his name from Ernst Hermann Bloch to Ernie Blake, believing that German prisoners would be more likely to cooperate with an interrogator who didn’t bear a Jewish surname. On D-Day, Second Lieutenant Ernie Blake flew to Europe, serving as an interpreter attached to General George Patton’s headquarters. His duties were both crucial and haunting: he interrogated approximately 200 German prisoners, including some of Hitler’s highest-ranking officials like Hermann Göring, Wilhelm Keitel, and Albert Speer. Most significantly, he was among the first Allied personnel to encounter Nazi concentration camps during Patton’s advance across Germany in 1945—an experience that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

The Search for the Perfect Mountain

After the war, Ernie and Rhoda Blake returned to the American West, where Ernie took on the management of Santa Fe Ski Basin in 1949. This position required him to also oversee operations at the sister resort in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, creating what would prove to be a fateful commuting arrangement.

After the war, Ernie and Rhoda Blake returned to the American West, where Ernie took on the management of Santa Fe Ski Basin in 1949. This position required him to also oversee operations at the sister resort in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, creating what would prove to be a fateful commuting arrangement.

Rather than enduring the lengthy drive between the two locations—a journey that consumed more than six hours each way—Blake purchased a Cessna 170 and took to the skies. These flights served a dual purpose: they saved precious time, but more importantly, they allowed Blake to study the terrain below with the eye of an experienced skier and resort operator. From his cockpit, he could analyze snow conditions, assess mountain aspects, and search for what he called “the spot”—the perfect location for his own ski resort.

On one such flight in 1953, Blake’s trained eye caught sight of something extraordinary. Nestled just north of Wheeler Peak, New Mexico’s highest point at 13,161 feet, lay a pristine basin with everything he had been seeking. The location offered steep slopes with extreme pitches, a crucial northern exposure that would preserve snowpack throughout the winter, and proximity to the culturally rich town of Taos, just 20 miles away. The site had another advantage—it was the location of Twining, a long-abandoned copper and gold mining settlement from the late 1800s, meaning some basic infrastructure remnants already existed.

From Mining Camp to Mountain Resort

In 1954, Blake took the leap that would define his legacy. He purchased the old mining claim of 80 acres and moved his family into an eleven-foot camper at what would become Taos Ski Valley’s base. The only existing structure was the nearly completed Hondo Lodge, which had been left unfinished with no windows or doors. This shell of a building particularly appealed to Blake, who had been frustrated by the lack of lodging facilities at Santa Fe Ski Basin.

The work of creating a ski resort from raw wilderness began immediately, with Blake, Rhoda, and their children clearing the land by hand and mule. The challenges were immense: securing permits from the National Forest Service, carving ski runs through dense forest, obtaining equipment, and hiring staff—all while operating in a location more than three hours from the nearest significant city, Albuquerque.

Many thought Blake’s vision was foolish. The established ski market was in Colorado, and Taos seemed impossibly remote. But Blake’s persistence and eye for quality terrain began to pay dividends. By 1956, the resort’s first lift—a J-bar surface tow—was installed, and the first run, Snakedance, cut its way down the mountain. This inaugural slope was no gentle beginner trail; Snakedance was a black diamond run that immediately announced Taos Ski Valley’s intentions to cater to serious skiers.

Many thought Blake’s vision was foolish. The established ski market was in Colorado, and Taos seemed impossibly remote. But Blake’s persistence and eye for quality terrain began to pay dividends. By 1956, the resort’s first lift—a J-bar surface tow—was installed, and the first run, Snakedance, cut its way down the mountain. This inaugural slope was no gentle beginner trail; Snakedance was a black diamond run that immediately announced Taos Ski Valley’s intentions to cater to serious skiers.

The following year brought crucial expansions that would establish the resort’s character. A Poma platter lift was added, and a second slope opened: Al’s Run, named after Dr. Al Rosen, a politically connected Taos surgeon who proved instrumental in the resort’s early success. Dr. Rosen was legendary for skiing with an oxygen mask and tank on his back until his death in 1982, embodying the kind of dedicated, no-compromise attitude that would define Taos skiing culture.

Al’s Run quickly gained notoriety as one of the most challenging continuous mogul runs in North America. With an average pitch of 30 degrees and stretching the entire length of Lift 1, it became both a rite of passage and a litmus test for skiers’ abilities. The run was so narrow that there was barely enough room for skiers descending and riders ascending on the surface lift. As one reviewer noted, “Your legs and lungs will be screaming when you get to the bottom, but such a feeling of exhilaration!”

The European Touch in American Mountains

Blake’s vision extended far beyond simply creating difficult terrain. Drawing on his European background and the influence of friends like French ski champion Jean Mayer, who arrived in 1957 to found the ski school, Blake sought to create an authentic mountain experience that blended traditional European hospitality with the rugged character of the American West.

The Blakes lived without electrical power until 1963, embodying the pioneering spirit they were instilling in their resort. Rhoda, who had served as an aircraft mechanic during World War II, handled the mechanical aspects of the operation, including mounting and tuning rental skis. The family’s commitment was total—Blake himself answered the phone and provided personal snow reports to prospective visitors planning weekend trips.

This hands-on approach created an intimacy that larger resorts couldn’t match. The Blake family’s continued ownership and operation helped preserve Taos Ski Valley’s unique character for nearly six decades, until the resort was sold to conservationist billionaire Louis Bacon in 2013.

The Terrain That Defines Legends

What truly set Taos Ski Valley apart was its uncompromising commitment to challenging terrain. More than half of the resort’s runs are rated expert or advanced, with a significant portion requiring hiking to access. The ski area encompasses 1,294 acres across 110 trails, but as the famous sign at the base reminds nervous visitors: “Don’t Panic! You’re Looking at only 1/30th of Taos Ski Valley. We have many easy runs too.”

The resort’s most legendary terrain lies in the hike-to areas along West Basin Ridge and Highline Ridge, where double-black diamond runs with names like Corner Chute, Stauffenberg, Fifth Chute, and Meatball challenge even the most skilled skiers. The crown jewel is Kachina Peak, rising to 12,481 feet and accessible via a lift that opened in 2015, though it had been a hike-to destination for decades before.

The mountain’s terrain is organized into six distinct areas, each with its own character. The Lower Front Side features the intimidating Al’s Run alongside more forgiving options, while the Upper Front Side offers scenic cruisers like Bambi and hidden chutes. The Back Side provides wide-open groomers and the resort’s terrain park, while the Highline Ridge and West Basin Ridge deliver the extreme terrain that has made Taos legendary.

As one longtime observer noted, “Taos is steeper than most Colorado areas [and] greater coverage is required” due to the technical nature of the terrain. The resort operates under what locals call the “75-inch rule”—the belief that at least 75 inches of base depth is necessary for optimal skiing on much of the expert terrain.

A Living Legacy in Autumn’s Golden Light

Today, as autumn paints the aspen groves in brilliant gold and the high peaks dust themselves with the season’s first snow, Ernie Blake’s vision continues to inspire new generations of mountain adventurers. The chilltravelers who venture into these mountains during fall find themselves in the capable hands of guides like Joe LeBlanc, whose four decades of experience in the Taos high country represent a living connection to Blake’s pioneering spirit.

LeBlanc, who has spent 40 years learning every fold and feature of these mountains, guides visitors on ATC (All-Terrain Cart) tours through the spectacular fall landscape. These adventures offer a different perspective on the same terrain that captivated Blake from his Cessna cockpit more than 70 years ago. Where Blake saw potential ski runs and snow retention, today’s visitors experience the raw beauty of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in their autumn glory—golden aspen stands giving way to evergreen forests, dramatic ridgelines stretching toward the distant horizon, and the same perfect northern exposures that convinced Blake he had found his mountain paradise.

The modern Taos Ski Valley continues to honor Blake’s vision while expanding opportunities for year-round mountain experiences. Summer activities include mountain biking on lift-served trails, via ferrata climbing routes that scale iron rungs and traverse dramatic skybridge at 11,500 feet on Kachina Peak, and scenic lift rides that showcase the stunning high-alpine environment. The resort’s commitment to being “better, not bigger” reflects Blake’s original philosophy of quality over quantity.

The Enduring Spirit of Innovation

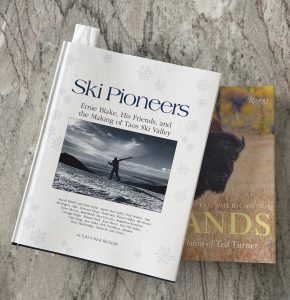

The story told in Rick Richards’ comprehensive book “Ski Pioneers: Ernie Blake, His Friends, & the Making of Taos Ski Valley” captures not just the biography of one man, but the essence of an era when visionary individuals could still carve their dreams directly into the landscape. Richards, who grew up with Taos Ski Valley and has extensive experience both as a skier and mountain guide, assembled interviews with some of the greatest names in skiing history to create what many consider the most detailed examination of Western ski history published in recent decades.

The story told in Rick Richards’ comprehensive book “Ski Pioneers: Ernie Blake, His Friends, & the Making of Taos Ski Valley” captures not just the biography of one man, but the essence of an era when visionary individuals could still carve their dreams directly into the landscape. Richards, who grew up with Taos Ski Valley and has extensive experience both as a skier and mountain guide, assembled interviews with some of the greatest names in skiing history to create what many consider the most detailed examination of Western ski history published in recent decades.

Through 22 chapters of reminiscences, humorous anecdotes, and commentary, supported by more than 250 historic photographs, the book reveals how Blake’s story interconnected with the broader development of American skiing. From the first runs at Sun Valley to the steeps of Taos, it recreates the pioneering journeys of the innovative skiers who shaped the sport we know today.

The book also illuminates the network of relationships that supported these early ski pioneers. Blake knew Friedl Pfeifer from Sun Valley and maintained friendships with Darcy Brown, one of the original investors in Aspen Ski Company. As Richards noted, “In the early days of skiing in America, it seemed everyone sort of knew everyone.” This interconnected community of ski pioneers shared knowledge, resources, and mutual support that proved crucial to the development of multiple resorts across the American West.

Blake’s influence extended beyond Taos to the broader skiing community. His commitment to authentic mountain experiences and uncompromising terrain standards helped establish expectations that continue to guide resort development today. The emphasis on ski instruction—with the Ernie Blake Snowsports School earning recognition as one of the highest-rated ski schools in North America—reflects his belief that technical skill should match the mountain’s demands.

Mountains as Teachers, Guides as Storytellers

When ChillTravelers join Joe LeBlanc for fall ATC tours through the Taos high country, they’re participating in a tradition that extends back to Blake’s earliest days of personally guiding visitors through his mountain domain. LeBlanc’s four decades of mountain experience echo Blake’s own intimate knowledge of every slope, every weather pattern, every subtle change in snow conditions that could affect the skiing experience.

These modern mountain tours reveal layers of history written in the landscape itself. The same mining roads that Blake first encountered when he purchased his 80-acre claim now serve as scenic routes for ATC adventures. The dramatic views that convinced Blake he had found the perfect ski location continue to inspire visitors who see them from new perspectives. The northern exposures that preserve winter snow also create unique microclimates that support diverse plant communities visible during autumn tours.

LeBlanc’s expertise in reading the mountain—understanding how weather patterns develop, where wildlife congregates, how seasonal changes affect the landscape—represents the same kind of intimate environmental knowledge that enabled Blake to envision a world-class resort in what others saw as merely rugged wilderness. These experienced guides serve as interpreters, translating the mountain’s subtle language for visitors who may be encountering high-alpine environments for the first time.

The chilltravelers experience connects them not only to the natural wonder of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains but to the human stories that have unfolded here. Blake’s journey from wartime refugee to ski resort visionary represents just one chapter in the larger narrative of how determined individuals have shaped America’s mountain recreation industry.

The Vision Endures

As the autumn sun sets behind Wheeler Peak, casting long shadows across the valley that Ernie Blake transformed from mining ghost town to skiing mecca, his legacy remains vibrantly alive. The resort continues to challenge skiers with terrain that demands respect and rewards skill, maintaining Blake’s original commitment to authenticity over accessibility.

As the autumn sun sets behind Wheeler Peak, casting long shadows across the valley that Ernie Blake transformed from mining ghost town to skiing mecca, his legacy remains vibrantly alive. The resort continues to challenge skiers with terrain that demands respect and rewards skill, maintaining Blake’s original commitment to authenticity over accessibility.

The chilltravelers who explore these mountains with guides like Joe LeBlanc are experiencing the same sense of discovery and adventure that drove Blake to purchase that first 80-acre mining claim in 1954. They see the landscape through the eyes of someone who understands its moods and rhythms, just as Blake learned to read snow conditions and weather patterns during his decades of mountain stewardship.

Modern visitors to Taos Ski Valley can still sense Blake’s presence in the resort’s unwavering commitment to challenging terrain and authentic mountain experiences. The sign warning visitors not to panic when they first see Al’s Run reflects Blake’s understanding that great skiing requires both humility and determination. The emphasis on ski instruction continues his belief that technical proficiency should match the mountain’s demands.

The story of Taos Ski Valley—from Ernie Blake’s wartime service and visionary leadership to today’s guided mountain adventures—demonstrates how individual passion and perseverance can create lasting institutions that continue to inspire new generations. As chilltravelers discover during their fall tours with veteran guides like Joe LeBlanc, the mountains remain as teachers, constantly offering new lessons to those willing to listen and learn.

In the end, Blake’s greatest achievement may not have been the ski runs he carved or the lifts he installed, but the culture of mountain appreciation and respect he established. The Taos Ski Valley motto of “improve everything but change nothing” encapsulates his vision of honoring the mountain while making it accessible to those ready to meet its challenges. This philosophy continues to guide the resort’s development and ensures that future generations of mountain adventurers—whether they arrive on skis, mountain bikes, or ATC tours—will encounter the same spirit of authentic mountain experience that Ernie Blake first envisioned in the high peaks of northern New Mexico.

Epilogue from the book, “Ski Pioneers.”

On January 21, 1989, at 12:30 p.m., thousands paid tribute to the memory of the man who founded Taos Ski Valley some thirty-three years ago. From Kirtland Air Force Base, two New Mexico National Guard Fighter Jets, led by Ernie’s long-time friend Captain Mike Rice and followed by Sandia ski patrolman Captain Dave Walker, took off on their mission. The two jets streaked across northern New Mexico, carrying the ashen remains of Ernie Blake for one last flight over the mountains he loved so dearly, tying over sandia, Santa Fe Ski Basin, Angel Fire, Rio Costilla, Red River and finally thundering up Taos Ski Valley. Thev made first one pass over The Valley, glided over the top of The Ridge, turned sharply above the Valdez. Rim and finally headed up Taos Ski Valley once again for Ernie’s last run. Over the jet’s radio, Captain Mike Rice spoke professionally to the ground crew, “Ready to jettison Ernie’s ashes approximately over the top of the #5 Lift.” But as the jets dipped their wings and rolled in the deep blue New Mexico sky scattering Ernie’s remains, in a different voice filled with a mixture of deep respect and love, Mike added a final, “Goodbye, old friend.” The Taos Ski Patrol gave honor to their general’s passing with a 21-gun salute from Highline Ridge, the guns being replaced more fittingly by 21 avalanche hand charges which resounded from mountain to mountain shattering the respectful hush of the valley below, echoing in the hearts of all who looked on. All took their special places to pay homage befitting a man who not only founded a magnificent ski area now rated in the top ten in the world, but who also created a winter economy for the once small village of Taos. Rhoda Blake, his wife, stood up above Zagava corner. Mickey, his eldest son, stood on the specially made platform below Lift #3 with Mayor Jeantete and other town dignitaries. At 12:30 p.m. the lift operators stopped all lifts out of respectful mourning for their loss. Simultaneously, other ski areas like Santa Fe and Rio Costilla shut down their lifts to pay their respects to this unforgettable man who was one of the first great pioneers of skiing in America.

Sometimes you visit a place and take a part of it with you. We took a big part of Ernie’s story with us as he is still alive in the hearts and minds of those that call Taos Ski Valley family. There is a deep lesson in those mountains.

Bob & Wendy

Our special video of the experience

Original Music by ChillTravelers

Be the first to comment