Jammin

By Bob Root

What do you get when you gather percussionists and exotic instrumentalists who worship Mickey Hart, Arthur Hull, and Babatunde together? An absolutely insane world beat jam.

In my living room, there is Wendy’s purple heartwood djembe hand drum made by Doug Soul, my handcrafted rosewood didgeridoo, and a rare Swiss hang drum. An absurd collection that symbolizes a bizarro world of potential. Add in found sounds and a group high on life, and you get this compilation of noises and sounds I call worldbeat meets astronaut.

In my living room, there is Wendy’s purple heartwood djembe hand drum made by Doug Soul, my handcrafted rosewood didgeridoo, and a rare Swiss hang drum. An absurd collection that symbolizes a bizarro world of potential. Add in found sounds and a group high on life, and you get this compilation of noises and sounds I call worldbeat meets astronaut.

So, let’s go way back in the 1990s. Wendy came to me on our boat home in San Diego and said, “We are going to Hawaii to learn to drum with Arthur Hull.” I just gazed with the first Gen Z stare ever recorded. ‘Why, because we need to and can.” Arriving in Honolulu, we were greeted with an antique school bus and a huge crowd of the craziest drummers you could imagine. A week of drumming under palm trees taught me that some people have a heartbeat at their soul’s life’s beat, and I did not. Mine was the sound of the didgeridoo. Arthur and I pondered whether music is in the beat or the spaces between the beats. Needless to say, we became friends and business partners for many years. Fast forward to my Frank Lloyd Wright house in Annapolis, Maryland. Late in the evening, amongst 60 acres of dense trees, Arthur played for the animals and us from our deck. Inspirational and other worldly. It was amazing to see the deer walk out of the deep forest just to listen to Arthur.

Still living in Annapolis, we got an invite to a unique world beat concert by Mickey Hart at a micro-venue downtown. Out rolled a driftwood sculpture half the size of the stage, and Mickey walked out and began to play on its branches: entrancement and entrainment.

Still living in Annapolis, we got an invite to a unique world beat concert by Mickey Hart at a micro-venue downtown. Out rolled a driftwood sculpture half the size of the stage, and Mickey walked out and began to play on its branches: entrancement and entrainment.

Back in LA, Arthur was to do a drum circle at REMO headquarters, and we were bound to surprise him. Besides all the shakers and drums was a lone Hang Drum—another life-changing moment. Babatunde was alive again that night and could be seen and felt through Arthur’s mastery.

Something brought back all those drum circles recently, which is the inspiration for this article and music collection. I think I was actually listening to Drops” by Mickey Hart, Zakir Hussain & Planet Drum from the album In the Groove is a hypnotic, trance-like percussion track blending global rhythms from Indian tabla, Nigerian talking drums, Puerto Rican congas, and processed sounds like raindrops into a primal, danceable groove. It slows the album’s energy, yielding expressive, layered polyrhythms that evoke nature’s organic pulse, with congas transformed into atmospheric effects and a steady, web-like percussive interplay that fosters a warm, meditative feeling.

I was inspired to pull together all the jives of this world beat collection for you. Said, this is not published anywhere, but a homage to the greatness of Arthur, Mickey, and Babatunde. To understand is to know these masters. Please, please, if you have the chance to join a real drum circle, it will be life-changing. At the very least, your life direction will change for the better.

So, here is a little about the masters.

Arthur Hull and the Magic of Village Music Drum Circles

Arthur Hull, often called the father of the community drum circle movement, has reshaped the way people connect through rhythm, community, and the shared magic of music-making. With an elf-like innocence and whimsical charisma, Hull’s Village Music Circles are far more than musical gatherings—they are potent spaces of transformation, joy, and healing, nurturing both individual and collective spirit in profound ways.

Arthur Hull, often called the father of the community drum circle movement, has reshaped the way people connect through rhythm, community, and the shared magic of music-making. With an elf-like innocence and whimsical charisma, Hull’s Village Music Circles are far more than musical gatherings—they are potent spaces of transformation, joy, and healing, nurturing both individual and collective spirit in profound ways.

The Heartbeat of Village Music: Arthur Hull’s Vision

What is a Village Music Circle?

A Village Music Circle is not just an event—it is a living community. Participants gather, regardless of experience or background, weaving simple rhythmic parts on drums, percussion, and other instruments. The process is joyous, egalitarian, and infused with Hull’s infectious energy. As he guides, laughter and silence mix, and the music becomes a communal force for unity and expression.

The “Elf-Like” Innocence and Authenticity

Central to Hull’s impact is his unmistakable personality—a blend of playful wisdom and gentle innocence, often described as elf-like. This demeanor immediately disarms newcomers, making everyone feel welcome. He doesn’t instruct in the traditional sense; rather, he “teaches without teaching,” inviting participants on a journey where discovery and creativity bloom in a safe, nonjudgmental space.

Hull’s presence animates drum circles with whimsical gestures, spontaneous humor, and a kind of magic that inspires all to let go and be their authentic selves. His facilitative style is gentle yet deeply skilled, blending musical mastery with a light-hearted spirit that catalyzes collective happiness and creativity.

The Feeling and Power of Drum Circles

Emotional Impact and Communal Transformation

Arthur Hull’s drum circles are renowned for the feeling they create. Unity, collaboration, emotional release, and healing arise naturally as participants connect with each other and the rhythm. Regardless of credentials, people join, laugh, play, and ultimately find themselves part of something greater—a single, living musical entity. Time seems to stop; worries disappear; and the raw joy of being together in rhythm takes hold.

Personal Stories: The Power to Uplift

Participants reflect on profound experiences: some arrive seeking peace, others connection, some pure fun or healing. Yet, all leave with a sense of revitalization, joy, and community. The circles have eased tensions between rival groups, healed emotional wounds, and brought strangers together in transformative acts of music.

Team building events, spirit-building sessions for personal growth, and community gatherings all attest to the circles’ power. The “pay back” from each event, as recounted by managers and participants, “continues to be visible,” strengthening bonds and improving communication long after the drum circle ends.

The Universal Language of Rhythm

Arthur Hull’s ethos is rooted in the belief that rhythm is the mother tongue. Every person—young or old, skilled or new—has something valuable to offer. By removing hierarchy and judgment, the drum circle becomes a place where diversity flourishes and every voice is heard. The drum’s pulse cuts across culture, age, and background, forging equality and understanding through shared music.

Arthur Hull’s ethos is rooted in the belief that rhythm is the mother tongue. Every person—young or old, skilled or new—has something valuable to offer. By removing hierarchy and judgment, the drum circle becomes a place where diversity flourishes and every voice is heard. The drum’s pulse cuts across culture, age, and background, forging equality and understanding through shared music.

Arthur Hull’s Facilitation Style: Whimsy and Wisdom

Facilitator as Community Midwife

Hull’s approach is more midwife than teacher. He listens deeply, intuitively responding to each circle’s needs. His tools are not rules, but rapport, eye contact, playful gestures, and subtle guidance. The goal is to move the group from a collection of individuals to a unified, synergized force—what Hull calls the Village Music Metaphor™.

“Teaching Without Teaching”: Exploration and Trust

Facilitation, for Hull, centers on making it easy for people to find their own rhythmical spirit. As participants play, explore, and create, Hull ensures judgment is left at the circle’s edge. This gentle trust-building unlocks freedom—empowering people to take risks, collaborate, and experience emotional release.

Community-Building and Healing

From Grassroots to Global Stages

Hull’s innovative techniques are sought worldwide, from corporate boardrooms to school classrooms, global festivals to local parks. His circles have brought together groups from five to thousands, proving the universality and scalable power of his approach.

Through intentional play and rhythmic entrainment, Hull’s circles give people a “rhythmical massage,” offering emotional release and healing tailored to each participant. Whether drumming, dancing, or even just watching, all are changed by the experience.

Testimonials: The Ongoing Ripple Effect

Testimonials: The Ongoing Ripple Effect

Participants routinely describe Hull’s events as the “most effective team building” experiences, crediting ongoing improvements in communication, trust, and collaboration. Others tell of personal transformation—from overcoming shyness to finding joy and peace through rhythm.

Arthur Hull: Legacy and Awards

Hull’s career spans more than four decades, including partnerships with renowned percussionists and global awards recognizing his impact on music and culture. His whimsical, spontaneous style continues to animate events worldwide, and his drum circle facilitation books and trainings have seeded a flourishing community of facilitators.

Basically

Arthur Hull’s Village Music drum circles are more than a musical event—they are a force for unity, healing, and joy. With elf-like innocence and unbounded playfulness, Hull crafts spaces where every person, regardless of age or background, can find resonance, support, and transformation. His circles teach us that the “mother tongue” of rhythm is the key to community—and that by drumming together, we become more whole, happy, and connected than we ever could alone.

Mickey Hart

Mickey Hart: From the Grateful Dead’s Rhythm Devil to Global Percussion Pioneer

Mickey Hart’s five-decade career represents one of music’s most profound journeys—a transformation from rock and roll percussionist to worldbeat visionary and ethnomusicological explorer. While Hart remains iconic for his nearly thirty years as one of the Grateful Dead’s two drummers, his equally significant legacy lies in his relentless pursuit to unlock the universal language of rhythm through world percussion, a mission that has elevated him to the status of a groundbreaking musical anthropologist and rhythmic philosopher.

Mickey Hart’s five-decade career represents one of music’s most profound journeys—a transformation from rock and roll percussionist to worldbeat visionary and ethnomusicological explorer. While Hart remains iconic for his nearly thirty years as one of the Grateful Dead’s two drummers, his equally significant legacy lies in his relentless pursuit to unlock the universal language of rhythm through world percussion, a mission that has elevated him to the status of a groundbreaking musical anthropologist and rhythmic philosopher.

The Foundation: From Rudimental Drummer to Rock Innovator

Mickey Hart’s connection to percussion runs deeper than most musicians’ commitment to their craft—it flows through his bloodline. Born September 11, 1943 , in Brooklyn, New York, Hart arrived into a family where drumming was not merely a hobby but a way of life. Both his parents were champion rudimental drummers, trained in the military marching-band tradition, and they had won the mixed doubles competition in rudimentary drumming at the World’s Fair. Hart describes his early imprinting with rhythmic sensibility in visceral terms: “In the womb, the bass is the heart,” he explains, noting that his mother’s heartbeat—at roughly 100 decibels—created an indelible rhythmic signature before he was even born.

His formal training began around age six or seven when his mother taught him the basic rudiments of drumming, grounding him in the disciplined technique that would form the foundation of his later explorations. However, Hart’s early education extended far beyond the confines of Western percussion traditions. Even as a young man, he was listening to Latin music, rainforest sounds, and African rhythms, immersing himself in a global soundscape that few Western musicians of his generation encountered. This early exposure to the world’s musical diversity would later prove prophetic, seeding what would become his life’s work.

Hart’s formal entry into professional music came through military service. Following high school, he enlisted in the United States Air Force in the early 0s, where he played in the prestigious Airmen of Note band. His stint lasted nearly four years and provided him with rigorous training and exposure to professional musicianship. The discipline of military bands—with their emphasis on precision, ensemble playing, and structured improvisation—would remain evident in Hart’s approach to percussion throughout his career.

At a Count Basie performance at The Fillmore in San Francisco, Hart encountered Bill Kreutzmann, the Grateful Dead’s original drummer. The meeting was fortuitous. Invited to jam with the Grateful Dead at a concert a few months later, Hart was captivated by the band’s experimental approach to rock music. In September, he officially joined the group, and his arrival marked a transformative moment in the Dead’s musical trajectory.

The Rhythm Devils Era: Expanding Rock’s Percussive Boundaries

With Hart’s addition, the Grateful Dead’s rhythmic palette underwent a dramatic expansion. Together, Hart and Kreutzmann became known as the “Rhythm Devils”—a moniker that captured their adventurous spirit and their commitment to extending percussion beyond conventional rock drumming. While Kreutzmann provided the steady, driving pulse that powered Dead concerts, Hart brought something distinctly different: an intellectual curiosity about rhythm itself and an appetite for exotic percussion instruments from around the world.

With Hart’s addition, the Grateful Dead’s rhythmic palette underwent a dramatic expansion. Together, Hart and Kreutzmann became known as the “Rhythm Devils”—a moniker that captured their adventurous spirit and their commitment to extending percussion beyond conventional rock drumming. While Kreutzmann provided the steady, driving pulse that powered Dead concerts, Hart brought something distinctly different: an intellectual curiosity about rhythm itself and an appetite for exotic percussion instruments from around the world.

Hart was not merely a Grateful Dead drummer; he was a student of percussion traditions across cultures. He studied tabla—the classical Indian drum—under Ustad Alla Rakha, the renowned accompanist to sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar. This study proved formative, introducing Hart to non-Western approaches to rhythm that fundamentally altered his musical thinking. The tabla’s complex metrical cycles and the deep philosophical underpinnings of Indian classical music opened new conceptual pathways for Hart’s explorations.

During the Dead’s “primal era” of –, Hart’s polyrhythmic interests became integral to the band’s arrangements. The Rhythm Devils’ extended drum duets and polyrhythmic explorations became hallmarks of Grateful Dead performances, introducing audiences to rhythmic possibilities far beyond the standard rock backbeat. Albums like Anthem of the Sun and Aoxomoxoa showcased Hart’s willingness to push the Dead into experimental sonic territory, with percussion serving as a vehicle for consciousness expansion rather than mere timekeeping.

Hart’s tenure with the Grateful Dead was not entirely uninterrupted. He left the band by mutual agreement in February , following a difficult period when his father—who briefly managed the group—embezzled funds from the band. This hiatus, however, would prove creatively generative, allowing Hart the space to pursue his worldbeat percussion interests without the demands of constant touring.

The Worldbeat Mission: From Diga to Planet Drum

Hart’s departure from the Grateful Dead in the early 0s coincided with the beginning of what would become his defining artistic mission: to break the rhythm code of the universe and explore the transcendent possibilities of percussion across all world cultures. This mission found its first major expression in the Diga Rhythm Band, founded in by Zakir Hussain at the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Francisco. When Hart joined in , the partnership between the American percussionist and the Indian tabla master began a musical conversation that would span decades.

Hart’s departure from the Grateful Dead in the early 0s coincided with the beginning of what would become his defining artistic mission: to break the rhythm code of the universe and explore the transcendent possibilities of percussion across all world cultures. This mission found its first major expression in the Diga Rhythm Band, founded in by Zakir Hussain at the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Francisco. When Hart joined in , the partnership between the American percussionist and the Indian tabla master began a musical conversation that would span decades.

The Diga Rhythm Band’s debut album represented a watershed moment in world music—the first significant attempt to marry Indian classical percussion with Western rock sensibilities and modern recording technology. Recorded at Hart’s studio The Barn in Novato, California, the album featured guest appearances by Jerry Garcia on guitar, lending Dead credibility to this groundbreaking venture. Diga was far ahead of its time, introducing Western audiences to the sophisticated polyrhythmic language of classical India while maintaining an accessibility that rock listeners could embrace. The album’s influence would ripple through progressive rock and world music for decades to come.

After Hart rejoined the Grateful Dead in , continuing with them until their dissolution in , his worldbeat percussion work progressed in parallel with his Dead commitments. The philosophical foundation was always clear: Hart believed that beneath the world’s extraordinary musical diversity lay “another, deeper realm” where “there is no better or worse, no pop music versus folk music, no distinctions at all, but rather an almost organic compulsion to translate the emotional fact of being alive into sound, into rhythm, into something you can dance to.”

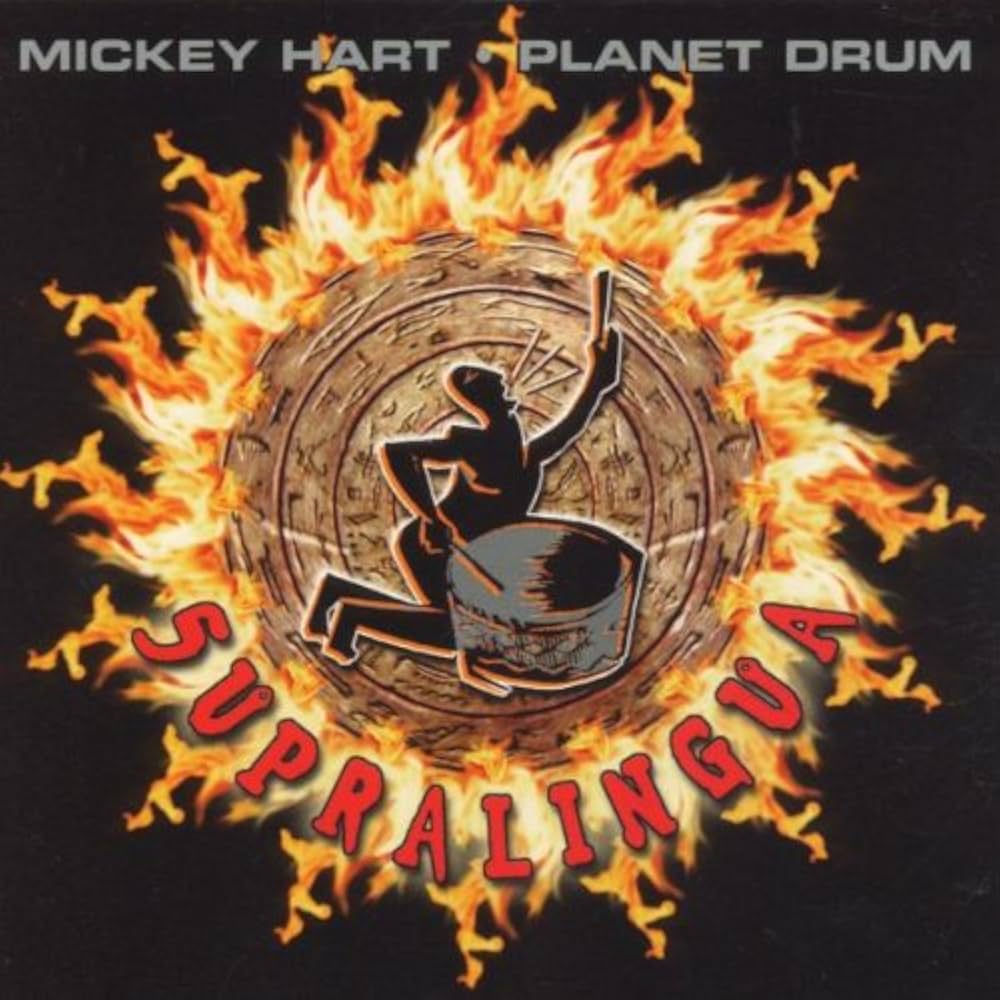

This philosophy crystallized in Planet Drum, released in . The project represented Hart’s most ambitious attempt to assemble a summit of global percussion masters who had never played together before. The lineup was remarkable: Zakir Hussain and T.H. “Vikku” Vinayakram from India, Babatunde Olatunji and Sikiru Adepoju from Nigeria, Airto Moreira and vocalist Flora Purim from Brazil, and Giovanni Hidalgo and Frank Colón from Puerto Rico, all brought together under Hart’s visionary guidance.0 Recording took place in Hart’s Sonoma County home studio, with the Dead’s legendary crew transforming virtually every room into a working space for individual musicians.

The result was nothing short of revolutionary. Planet Drum spent an unprecedented weeks at number one on the Billboard World Music Chart, and it won the very first Grammy Award for Best World Music Album in . The album’s success was not merely commercial; it was cultural and historical. Hart had introduced world music to millions of listeners who had no prior exposure to non-Western percussion traditions. People who had never heard a djembe, a talking drum, or Indian tabla suddenly encountered these instruments through the album’s hypnotic grooves.

Hart later reflected on this cultural moment with characteristic insight: “People sure know what a djembe is now. They’re everywhere. Even in Bali. I saw drummers playing them on the beach.” Back in , this accessibility to world percussion instruments was revolutionary. The album succeeded because Hart and his collaborators managed to create something neither purely traditional nor purely Western, but rather a new synthesis that honored both approaches while transcending their limitations.

The Philosophy of Percussion: Breaking the Rhythm Code

Central to Hart’s worldbeat work is an almost spiritual philosophy about rhythm and its role in human consciousness and cosmic order. Hart speaks of his mission as one of decoding the fundamental vibrations of existence itself. In his words: “The universe is made up of vibrations. I have been very interested in sonifying the universe, the cosmos, the sun, the Big Bang, taking those radiations from telescopes, radio telescopes, and turning that radiation into sound, which I make music out of and compose with.” This is not mere poetic metaphor; Hart has literally collaborated with astrophysicists to transform cosmic radiation into musical compositions.

Beyond astrophysics, Hart’s philosophy extends into neuroscience and medicine. In the 0s, Hart’s grandmother developed dementia and largely stopped communicating. When Hart played the drums for her, she spoke his name—a moment of profound clarity that convinced him of music’s therapeutic power. This personal experience propelled Hart toward serious scientific collaboration. Working with neuroscientist Dr. Adam Gazzaley at the University of California San Francisco, Hart has participated in groundbreaking research exploring how rhythm affects brain function. Their work suggests that certain rhythms might help wounded brains enter states of consciousness they can no longer sustain independently, with potential applications for stroke recovery, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, and ADHD.

Hart even appeared before the U.S. Senate Committee on Aging in August , speaking about the healing value of drumming and rhythm on age-related afflictions. This blend of artistic exploration, spiritual seeking, and scientific inquiry represents Hart’s unique contribution to contemporary culture. For Hart, rhythm is not entertainment; it is medicine, philosophy, cosmology, and consciousness technology all at once.

The Global Drum Project and Digital Innovation

Following Planet Drum’s success, Hart might have rested on his considerable laurels. Instead, he continued evolving. Fifteen years after Planet Drum, Hart reunited with his core collaborators—Zakir Hussain, Sikiru Adepoju, and Giovanni Hidalgo—to create the Global Drum Project, released in 00. This new project pushed Hart’s worldbeat vision into unexplored territory, blending traditional percussion with electronic programming, digital processing, and sampled sounds. The album won a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary World Music Album in 00, demonstrating that Hart’s vision remained vital and relevant across decades.

The Global Drum Project represented a significant evolution in Hart’s thinking. Where Planet Drum had emphasized the acoustic beauty of world percussion instruments, Global Drum Project embraced cutting-edge technology as a tool for musical innovation rather than a threat to acoustic authenticity. Hart viewed digital processing not as a compromise but as a natural extension of percussion’s evolutionary possibilities. The album’s tracks wove together traditional rhythms with electronic manipulation, creating what one reviewer described as “tranced-out grooves, elegant electronic programming and hypnotic tuned percussion.”

Hart’s embrace of technology culminated in the development of his Random Access Musical Universe (RAMU), a synthesizer-based system combining a sophisticated drum machine with Hart’s extensive personal library of sound samples collected over decades of world music exploration.0 RAMU, released as an album in 0, represented the culmination of Hart’s lifelong mission to merge ancient percussion traditions with st-century digital possibilities. The album featured contributions from contemporary artists including members of Animal Collective, creating a bridge between Hart’s world music foundation and cutting-edge contemporary music.

The Worldbeat Legacy and Cultural Impact

Mickey Hart’s significance to world music extends far beyond his albums and performances. He stands as one of the few Western musicians who achieved genuine cultural respect and collaboration within world music traditions. Zakir Hussain, one of the world’s greatest tabla players, remained Hart’s collaborator and friend for over 0 years—a relationship that speaks to the depth of mutual respect between them. Hart didn’t appropriate world music; he humbly approached it as a student, engaging with master musicians as colleagues and teachers.

Hart’s written work also contributed significantly to worldbeat consciousness. Drumming at the Edge of Magic (0) and Planet Drum: A Celebration of Percussion and Rhythm ()—co-written with Fredric Lieberman and D.A. Sonneborn—became standard references for understanding percussion’s role across world cultures. These lavishly illustrated volumes moved beyond mere technical instruction to explore the spiritual and cultural dimensions of drumming across civilizations.

Beyond artistic achievement, Hart became an advocate for music therapy and the medicinal applications of rhythm. His work with Dr. Gazzaley has contributed to scientific understanding of how rhythm influences brain function, potentially opening new therapeutic avenues for neurological conditions. Hart also championed the Smithsonian Folkways collection of world music recordings, positioning himself as a preservationist of global percussion traditions.

The Grateful Dead and Worldbeat: A Unified Vision

It is important to recognize that Hart’s work with the Grateful Dead and his worldbeat mission were never truly separate endeavors. Instead, they represented different expressions of a unified philosophy about rhythm, consciousness, and cultural synthesis. The Dead’s improvisational approach and willingness to incorporate diverse musical influences created a natural home for Hart’s worldbeat explorations. Conversely, Hart’s experiences with world percussion traditions directly enriched the Dead’s sound.

When Hart returned to perform with surviving Grateful Dead members during the Fare Thee Well 0th-anniversary tour in 0, he and Bill Kreutzmann reprised the “Rhythm Devils” segment, showcasing decades of evolved percussion dialogue that now incorporated everything Hart had learned from world music traditions. Similarly, his ongoing work with Dead & Company continues to incorporate worldbeat elements, demonstrating that Hart has never compartmentalized his musical interests.

The Unfinished Journey

Mickey Hart stands as a towering figure in late 0th and early st-century music—equally significant as a Grateful Dead legend and as a pioneering explorer of world percussion. His trajectory from rudimental drummer to rhythm philosopher represents a rare synthesis of artistic ambition, intellectual curiosity, and spiritual seeking. Through Planet Drum, the Global Drum Project, his scientific collaborations, and his written work, Hart has fundamentally altered how millions of people understand and relate to rhythm and percussion.

Hart’s worldbeat mission transcends mere musical tourism or cross-cultural appropriation. Instead, it represents a genuine belief that rhythm represents a universal language beneath cultural particularities—a vibration that connects all humanity across time and space. Whether performing Rhythm Devils duets with Bill Kreutzmann at a Grateful Dead concert, composing music from cosmic radiation with astrophysicists, collaborating with neuroscientists on rhythm’s healing properties, or recording albums with master percussionists from around the world, Hart has demonstrated unwavering commitment to this vision.

At over eighty years old, Hart continues recording, performing, and innovating. His most recent work, including the Planet Drum album In the Groove (0), shows no sign of diminishment, instead reflecting an artist still exploring new possibilities within his core mission. Mickey Hart’s history as the Grateful Dead’s drummer provides the platform for his worldbeat work, but his legacy ultimately rests on his willingness to venture beyond rock and roll into the deeper mysteries of rhythm itself.

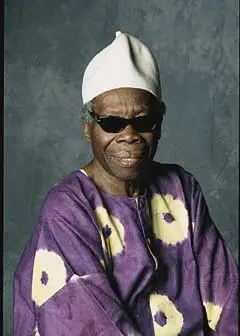

Babatunde Olatunji: The Father of African Drumming and His Revolutionary Teaching Method

Born Michael Babatunde Olatunji in in Ajido, Nigeria, this visionary percussionist became known as “Baba” to his legions of students and admirers worldwide. His groundbreaking work fundamentally transformed how Western audiences understood African music and established the foundation for the modern community drumming movement. Through his innovative ” gun, go do, pa ta” phonetic teaching method, Olatunji made the complex art of African drumming accessible to anyone willing to learn, while his collaborations with Arthur Hull and Mickey Hart created lasting legacies that continue to resonate through music education and world percussion today.

Born Michael Babatunde Olatunji in in Ajido, Nigeria, this visionary percussionist became known as “Baba” to his legions of students and admirers worldwide. His groundbreaking work fundamentally transformed how Western audiences understood African music and established the foundation for the modern community drumming movement. Through his innovative ” gun, go do, pa ta” phonetic teaching method, Olatunji made the complex art of African drumming accessible to anyone willing to learn, while his collaborations with Arthur Hull and Mickey Hart created lasting legacies that continue to resonate through music education and world percussion today.

From Nigerian Village to American Stages

Olatunji’s childhood was steeped in the rhythmic traditions of Yoruba culture. Growing up in a small fishing village about forty miles from Lagos, he later wrote in his autobiography: “I heard the drum while I was in my mother’s womb. I woke up every day to the beat of the drum” . Though his father, a fisherman who had been groomed for chieftaincy, died just before Olatunji’s birth, the young man absorbed the drumming that accompanied every aspect of village life—from dawn ceremonies to marketplace celebrations to naming rituals.

In 0, Olatunji received a Rotary International scholarship to attend Morehouse College in Atlanta, originally intending to become a diplomat for his people. What he encountered there shocked him. His classmates harbored profound misconceptions about Africa, asking whether lions roamed the streets and whether Africans had tails. This dangerous ignorance ignited his mission. “Africa had given so much to world culture, but they didn’t know it,” he recalled. “I decided to educate my colleagues about Africa “. He began hosting informal gatherings in his dormitory room, playing African music and explaining its connections to blues, jazz, and even the music of Cuban bandleader Ricky Ricardo on I Love Lucy—which featured actual Yoruba folk songs.

By , Olatunji organized his first formal performance of African music and dance at Morehouse, a groundbreaking event that drew white audiences from downtown Atlanta. After graduating in with a degree in Political Science, he moved to New York City to pursue graduate studies at NYU while working in a ball-point pen factory and helping build the Ford Motor plant in New Jersey to support himself.

The Album That Changed Everything

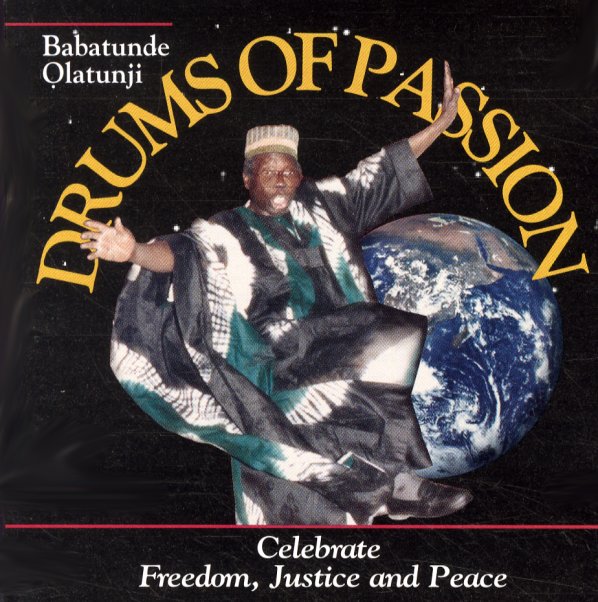

Olatunji’s trajectory shifted dramatically in when he collaborated with Radio City Music Hall arranger Raymond White on “African Drum Fantasy,” which played four shows daily for seven weeks. In the audience was Al Han, an executive from Columbia Records, who immediately signed Olatunji to a recording contract. The result was Drums of Passion, released in February 0—a revolutionary album that became the first recording to bring authentic African music to Western ears in a modern studio production.

Olatunji’s trajectory shifted dramatically in when he collaborated with Radio City Music Hall arranger Raymond White on “African Drum Fantasy,” which played four shows daily for seven weeks. In the audience was Al Han, an executive from Columbia Records, who immediately signed Olatunji to a recording contract. The result was Drums of Passion, released in February 0—a revolutionary album that became the first recording to bring authentic African music to Western ears in a modern studio production.

Drums of Passion proved immensely successful, eventually selling over five million copies and climbing to number on the Billboard charts. The album featured Olatunji’s masterful arrangements for drummers and vocalists, including the signature song “Jin-Go-Lo-Ba,” which would later be covered by Carlos Santana as “Jingo” and become one of his band’s signature hits. The recording showcased the call-and-response patterns central to African musical tradition while incorporating elements of American blues and jazz. In 00, the album was inducted into the National Recording Registry, cementing its status as a cultural landmark.

Despite its commercial success, Olatunji never profited from the original release. “I never made any money from that recording until I met a very fine lawyer named Bill Krasilozcky,” he said with evident sadness. “He helped me regain ownership of the title Drums of Passion after twenty years” .

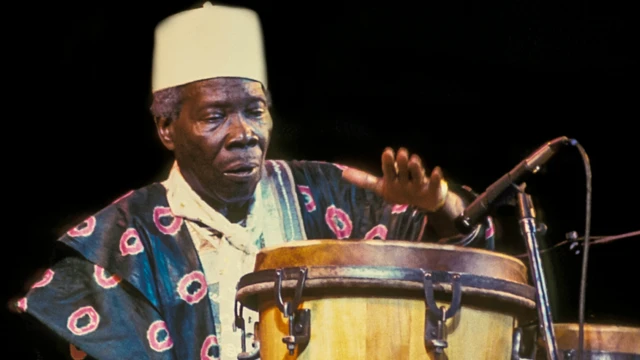

Revolutionary Educator and Cultural Ambassador

Throughout the 0s, Olatunji became a ubiquitous presence in American culture, appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and The Mike Douglas Show. More significantly, he established deep connections within the jazz community, performing at Birdland with a combo that opened for Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Quincy Jones. His ensemble included legends like Yusef Lateef, Clark Terry, Coleman Hawkins, Horace Silver, Dizzy Gillespie, and John Coltrane.

The relationship between Olatunji and John Coltrane proved particularly profound. With Coltrane’s financial support—he donated $0 monthly—Olatunji founded the Olatunji Center for African Culture in Harlem in 0. The center offered classes in African dance, music, language, folklore, and history for just two dollars per class, along with a teacher training program and the Sunday “Roots of Africa” concert series featuring performances by Coltrane, Yusef Lateef, and Pete Seeger. Coltrane composed the piece “Tunji” on his album Coltrane as a dedication to his mentor, and performed his final concert at the Olatunji Center in .

Despite support from the Rockefeller family ($,000) and individual artists, the center struggled financially. The Ford Foundation rejected Olatunji’s grant application, stating “We don’t fund your kind of program” . Olatunji had to recruit children off the streets to participate in Saturday programs because well-to-do Black families wouldn’t bring their children to Harlem. After years of fighting to maintain the lease, the center finally closed in .

The Gun, Go Do, Pa Ta Method: Revolutionary Drumming Pedagogy

Olatunji’s most lasting educational contribution emerged from his systematic approach to teaching African drumming. In his instructional video Babatunde Olatunji: African Drumming, he explained his famous ” gun, go do, pa ta” phonetic method, which he described as “the easiest and fastest way you can learn how to play the drum” .

Olatunji’s most lasting educational contribution emerged from his systematic approach to teaching African drumming. In his instructional video Babatunde Olatunji: African Drumming, he explained his famous ” gun, go do, pa ta” phonetic method, which he described as “the easiest and fastest way you can learn how to play the drum” .

The method derived directly from consonant sounds in the Yoruba language, using six vocal syllables to represent drum tones: Gun (pronounced “goon”), Doon, Go, Do, Pa, and Ta. Each syllable corresponded to a specific hand technique and tonal quality on the drum. Olatunji emphasized: “Those are the sounds we’re going to deal with. So if you can sing it, you can play it. That’s what I said. If you can sing it or say it, you can play it on the drum” .

The “Gun” or “Goon” sound represented the deepest bass tone, produced by striking the center of the drumhead with the full hand, fingers together and relaxed. As Olatunji explained: “The goon sound is always in the middle of the drum. Never any place will you ever get another sound on the drum that will be more than what you get on the middle of the drum” .

The “Go Do” sounds created mid-range tones played on the edge of the drumhead, with hands positioned between the center and rim. Olatunji stressed the importance of proper hand placement: “It’s extended from the middle of middle finger to this part of your hand on both hands… if I do place hands between first and second joint I will be hitting on the rim of the drum and that hurts “.

The “Pa Ta” sounds produced the sharp, slapping tones achieved by tilting the hand at an angle reminiscent of a karate strike and brushing across the drumhead surface. Olatunji noted this was perhaps the most challenging technique: “This is probably the one that you will have to really work on… it will take time, persistency and patience to get your part to sound like mine” .

When asked about his logical and systematic teaching approach, Baba characteristically deflected recognition: “I must give credit where credit is due. It was there all along! It comes from the consonants in the Yoruba language. I didn’t invent the system. I just discovered it “.

This phonetic method proved revolutionary because it bypassed the need for Western musical notation or years of cultural immersion. Students could vocalize rhythmic patterns and immediately translate them to the drum, making African drumming accessible to anyone regardless of musical background.

The Grateful Dead Connection: Mickey Hart’s Mentor

Perhaps no relationship better illustrates Olatunji’s far-reaching influence than his connection with Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead. The story began in the 0s when Olatunji performed educational demonstrations at elementary schools on Long Island, New York0. During these performances, he would invite students to join him on stage. One young boy who participated was Mickey Hart, then a student at an elementary school where Olatunji appeared.

Perhaps no relationship better illustrates Olatunji’s far-reaching influence than his connection with Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead. The story began in the 0s when Olatunji performed educational demonstrations at elementary schools on Long Island, New York0. During these performances, he would invite students to join him on stage. One young boy who participated was Mickey Hart, then a student at an elementary school where Olatunji appeared.

“I raised his hand and said, ‘He’s good!’” Olatunji recalled. That brief encounter planted a seed that would shape Hart’s entire musical trajectory. As Hart later discovered Olatunji’s recordings, particularly Drums of Passion, the Nigerian master became one of his formative influences.

The relationship came full circle in November when Hart approached Olatunji following a concert in San Francisco. “You probably don’t remember me,” Hart said, “but you are the reason I’m playing drums today” . Hart immediately invited Olatunji to open for the Grateful Dead at their New Year’s Eve concert at the Oakland Coliseum on December , 0. That performance, which came after nearly two decades of relative obscurity for Olatunji, marked a watershed moment.

“When I think of that night, it gladdens my heart,” Olatunji proclaimed. Hart recognized the potential for collaboration and began producing recordings for his mentor. Starting in , they created Drums of Passion: The Invocation, a collection of Yoruba tribal devotions to various orishas (deities), with Hart producing and occasionally accompanying on hoop drum and concussion stick0. This was followed by Drums of Passion: The Beat in , which featured contributions from Airto Moreira and Carlos Santana.

Planet Drum: A Grammy-Winning Collaboration

The pinnacle of Hart and Olatunji’s partnership came with Planet Drum, released in . Hart’s concept was ambitious: bring together master percussionists from around the world to create a new global sound that incorporated diverse musical styles and traditions. The ensemble included Hart from the United States, Zakir Hussain and T.H. “Vikku” Vinayakram from India, Sikiru Adepoju and Babatunde Olatunji from Nigeria, Giovanni Hidalgo and Frank Colón from Puerto Rico, and Airto Moreira and vocalist Flora Purim from Brazil.

Planet Drum proved groundbreaking. It won the Grammy Award for Best World Music Album of —the first year the category existed—and spent an unprecedented weeks at number one on the Billboard World Music chart. The album demonstrated that percussionists from vastly different traditions could create something greater than the sum of their parts, with Nigerian talking drums conversing with Indian tablas and Brazilian surdos.

Following the album’s success, the ensemble toured nationally, playing sold-out shows at venues including Carnegie Hall. As Mickey Hart reflected in a interview: “We spoke the same language. It was about rhythm—the drums—and he was the godfather of this whole movement of communal drumming” .

Arthur Hull: The Protégé Who Transformed Community Drumming

While Hart brought Olatunji’s music to massive audiences, another student would transform Baba’s educational philosophy into a worldwide movement. Arthur Hull, described as “a protégé of Babatunde Olatunji,” is credited with originating and defining modern-day Drum Circle Facilitation0.

While Hart brought Olatunji’s music to massive audiences, another student would transform Baba’s educational philosophy into a worldwide movement. Arthur Hull, described as “a protégé of Babatunde Olatunji,” is credited with originating and defining modern-day Drum Circle Facilitation0.

Hull’s relationship with Olatunji began during the “Summer of Love” in San Francisco. While serving in the military, Hull would spend his weekend leaves studying with percussionists, including visits to “Hippie Hill” at the end of the Panhandle near Haight-Ashbury, where anarchic drum circles formed spontaneously. Hull absorbed both the structured techniques of traditional African and Afro-Cuban drumming and the free-form energy of these countercultural gatherings.

Through his studies with Olatunji, Hull learned what he calls “the heart” and “the true meaning of suonare le percussioni” (playing percussion). Olatunji’s influence shaped Hull’s understanding of rhythm as a communal, spiritual practice rather than merely a technical skill. As Hull explained in a podcast interview: “Babatunde Olatunji, uno dei miei maestri, quello che mi ha insegnato il cuore… aveva una missione, e la sua missione era di mettere un tamburo in ogni casa” (Babatunde Olatunji, one of my teachers, the one who taught me the heart… had a mission, and his mission was to put a drum in every house).

Hull carried forward Olatunji’s mission but transformed the method. He founded Village Music Circles, through which he instructed thousands of students at the University of California, Santa Cruz, while simultaneously bringing experiential team-building and leadership events to organizations internationally. His innovation was the concept of “teaching without teaching “—a facilitation approach that creates space for participants to discover their own musical potential rather than imposing rigid instruction.

Hull carried forward Olatunji’s mission but transformed the method. He founded Village Music Circles, through which he instructed thousands of students at the University of California, Santa Cruz, while simultaneously bringing experiential team-building and leadership events to organizations internationally. His innovation was the concept of “teaching without teaching “—a facilitation approach that creates space for participants to discover their own musical potential rather than imposing rigid instruction.

The Village Music Circles method guides facilitators through four progressive stages: Dictator (establishing basic signals and group norms), Director (sculpting the group’s attention toward musical elements), Facilitator (guiding participants toward “Percussion Ensemble Consciousness”), and Orchestrator (taking the group on musical journeys they couldn’t achieve independently). This protocol allows even complete beginners to participate meaningfully in creating complex, layered rhythms within a single session.

Hull’s philosophy directly echoes Olatunji’s egalitarian approach: “Anyone who does something so great that he or she can never be forgotten has become an Orisha,” Olatunji said. Similarly, Hull emphasized that facilitators should work themselves out of a job—“your job description of a drum circle facilitator is to fire yourself because they don’t need you anymore” .

Through his Village Music Circles training programs, Hull has now taught people in many countries how to facilitate rhythm-based events. Over ninety percent of REMO-endorsed facilitators have graduated from Arthur’s training. He has received numerous awards, including the Santa Cruz Calabash Award and Drum Magazine’s Drummie Award for Best Drum Circle Facilitator.

Hull’s work has touched diverse populations, from corporate executives at Lucent Technology, Walt Disney, Pac Bell, Cisco Systems, and Sun Microsystems to street gangs, children at risk, and participants at holistic healing conferences. His books Drum Circle Spirit: Facilitating Human Potential Through Rhythm and Drum Circle Facilitation serve as handbooks for his courses and have become foundational texts in the field.

Importantly, Hull’s facilitated drum circles are specifically non-culturally specific. While African djembes may predominate, participants use drums and percussion from many traditions. This approach honors Olatunji’s vision of rhythm as a universal language while avoiding cultural appropriation—participants create their own in-the-moment rhythms rather than attempting to replicate traditional patterns they haven’t earned the right to play.

Legacy and Lasting Influence

Babatunde Olatunji passed away 1n April—one day before his birthday—at Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital near the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, where he had taught for nearly years. His daughter reported that he died from complications of diabetes. Two years earlier, in 00, he had been inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame alongside early New Orleans drummer Baby Dodds and Armenian cymbal maker Avedis Zildjian.

His influence radiates through multiple generations and genres. John Coltrane dedicated “Tunji” to him and relied on his musical and financial support. Bob Dylan referenced him in the lyrics of “I Shall Be Free” on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan: “What I want to know Mr. Football Man, is what do you do about Martin Luther King? Willie Mays? OLATUNJI?”. Carlos Santana transformed Olatunji’s “Jin-Go-Lo-Ba” into his signature hit “Jingo”. Spike Lee commissioned him to create music for She’s Gotta Have It0.

Perhaps most significantly, Olatunji helped establish the foundations for what would become known as world music as a commercial category. Before Drums of Passion, Western record companies produced “exotica” recordings—studio confections that created imagined soundscapes of “faraway lands” without authentic cultural input. Olatunji’s work demonstrated that genuine African music could find commercial success and critical acclaim in Western markets, opening doors for countless artists who followed.

His educational philosophy transformed how drumming could be taught and shared. The gun, go do, pa ta method made African rhythms accessible to students worldwide, while his broader vision—that rhythm is the soul of life and a tool for building community—became the animating principle of the modern drum circle movement. Through Arthur Hull’s work, that vision now reaches tens of thousands annually.

His educational philosophy transformed how drumming could be taught and shared. The gun, go do, pa ta method made African rhythms accessible to students worldwide, while his broader vision—that rhythm is the soul of life and a tool for building community—became the animating principle of the modern drum circle movement. Through Arthur Hull’s work, that vision now reaches tens of thousands annually.

Mickey Hart articulated Olatunji’s significance powerfully: “We spoke the same language. It was about rhythm—the drums—and he was the godfather of this whole movement of communal drumming” . That movement continues to grow, carrying forward Baba’s mission to put a drum in every house and to use rhythm as a force for education, healing, and human connection.

As Olatunji himself proclaimed in his signature phrase, which captures the essence of his life’s work: “I am the drum, you are the drum, and we are the drum. Because the whole world revolves in rhythm, and rhythm is the soul of life, for everything that we do in life is in rhythm” . Through his groundbreaking recordings, revolutionary teaching methods, and the work of devoted students like Mickey Hart and Arthur Hull, Babatunde Olatunji ensured that this rhythmic wisdom would continue to pulse through generations yet to come.

###

ChillTravelers Homage To The Masters

These tracks are pure jam with the exception they have fade in and fade out plus EQ10 settings to make them publishable.

Be the first to comment